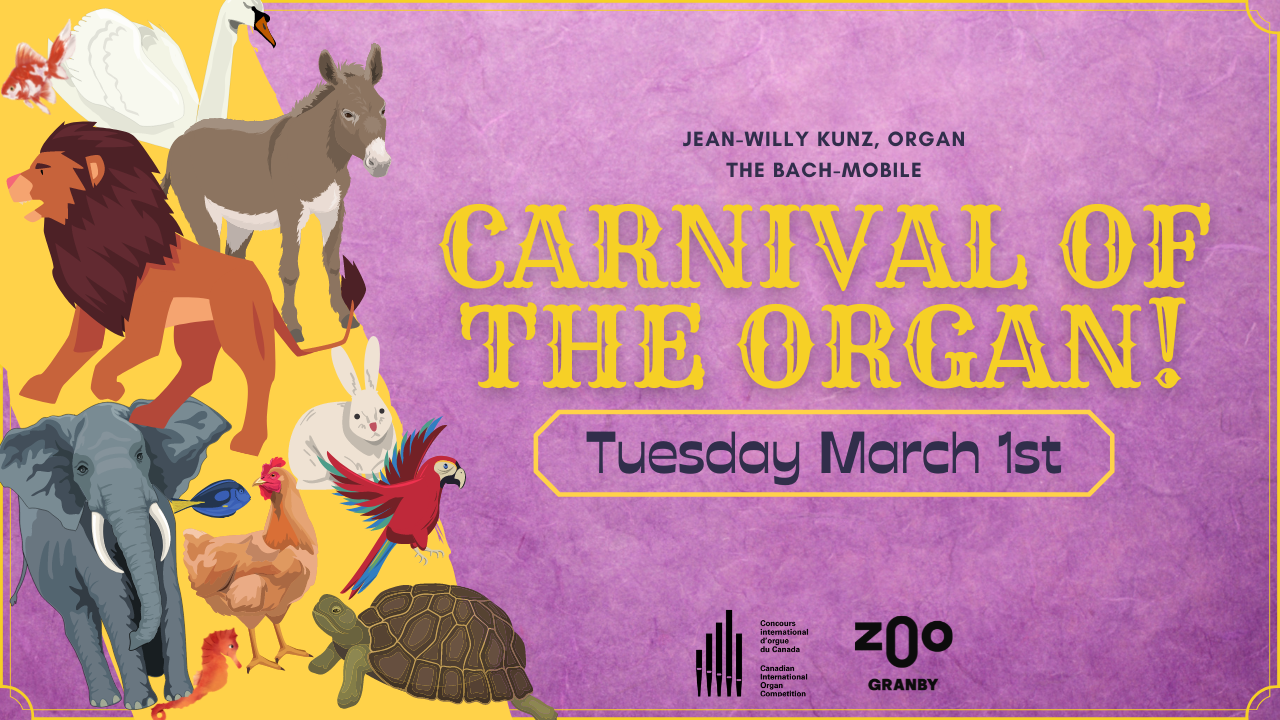

The CIOC and the Bach-Mobile took a field trip to Granby Zoo for a special performance of Camille Saint-Saëns’ The Carnival of the Animals (Le Carnaval des animaux). Transcribed for organ by Jean-Willy Kunz, the movements take us on a tour of the animal kingdom as we explore Granby Zoo on the CIOC’s Bach-Mobile.

Premiering at 7PM on YouTube and Facebook

Program Notes:

Despite his general deference towards serious music structured in traditional forms, Camille Saint-Saens was not without a sense of musical humour. Many of Saint-Saens’ works, in particular works for the theatre and programmatic instrumental music display the composer’s penchant for cleverly rendering extra-musical subjects through music, and in The Carnival of the Animals this penchant is taken to extreme (and hilarious) lengths. Evidence suggests that Saint-Saens may have conceived of writing a humorous suite with a zoological subject as early as the 1860’s, however work on The Carnival of the Animals did not begin until 1886, at the same time as the composer was working on his monumental Third Symphony, featuring a prominent part for pipe organ.

Each of the fourteen movements of The Carnival of the Animals musically depicts a particular animal or group of animals, masterfully making use of musical gestures, articulations, and textures to illustrate the sounds, movements, and/or appearances of each animal. Some of the movements also quote music by other composers and well-known folk tunes, often in the context of a musical joke adding further layers of wit to the piece. A couple of the movements feature outright satire – depicting music critics as braying donkeys and pianists as caged animals!

While there were several private performances following the work’s completion, Saint-Saens feared that publication of the work within his lifetime would damage his reputation as a composer of serious music, and thus The Carnival of the Animals was not published until 1922, a year after the composer’s death. When the first public performance was given that same year, it was received with immense enthusiasm, and since then it has become one of the best-known and most frequently performed works of Saint-Saens. The review by Le Figaro following that first performance aptly recounts the work’s popularity with the public:

We cannot describe the cries of admiring joy let loose by an enthusiastic public. In the immense oeuvre of Camille Saint-Saëns, The Carnival of the Animals is certainly one of his magnificent masterpieces. From the first note to the last it is an uninterrupted outpouring of a spirit of the highest and noblest comedy. In every bar, at every point, there are unexpected and irresistible finds. Themes, whimsical ideas, instrumentation compete with buffoonery, grace and science. … When he likes to joke, the master never forgets that he is the master.

- I. Introduction et Marche royale du lion

Following a brief introductory passage, the lion’s entrance is announced by a fanfare fitting for the King of Beasts. A pompous and vigorous march ensues, within which the lion’s tremendous roar is heard, represented musically by growling chromatic passages in the low register.

- II. Poules et coqs

The first of several references to works of other composers is heard in this movement, which uses a motive from Jean-Philippe Rameau’s piece for harpsichord entitles La Poule. In contrast to Rameau’s elegant piece, Saint-Saens’ reinterpretation conjures up a frenzy, depicting the commotion of a busy chicken coop. The chickens’ incessant pecking and clucking builds in intensity until the movement ends suddenly with a fortissimo chord.

- III. Hémiones (animaux véloces)

This short movement in moto perpetuo features rapid gestures up and down the full range of the keyboard, depicting a herd of wild donkeys relentlessly racing across the landscape.

- IV. Tortues

As animals known for their unhurried pace, the tortoises are illustrated by a musical joke: Jacques Offenbach’s Infernal Galop, a piece meant to be played at full-tilt, is reduced to a sleepy dirge.

- V. L’éléphant

More musical humour is featured here: fragments from the scherzo of Mendelssohn’s incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream as well as from Berlioz’ Dance of the Sylphs from The Damnation of Faust are fashioned by Saint-Saens into a bumbling waltz. While the musical quotations in their original contexts are played gracefully and in the high register, they are played here in the lowest register and with a weighty awkwardness that aptly describes the elephant’s unwieldly gait.

- VI. Kangourous

Despite weighing up to 90 kg, kangaroos have legs and feet well adapted for leaping, a motion they are able to execute with seeming effortlessness. This leaping motion can be heard throughout the movement.

- VII. Aquarium

The other-worldly quality of the music in this movement takes the listener below the surface of the water, evoking images of colourful coral reefs, kelp gently swaying in the waves, and fish and aquatic creatures of all sorts quietly going about their business.

- VIII. Personnages à longues oreilles

The « characters » featured in this movement are quite obviously donkeys, though some speculate that the musical banter here goes further: The crude hee-haw of the donkey may parallel the aggravating didacticism of a mud-slinging music critic.

- IX. Le coucou au fonds des bois

The quiet chorale-like harmonies of this movement help establish a forest-like setting, with towering tree columns supporting a canopy vault reminiscent of a great cathedral. The descending major third characteristic of the Cuckoo bird’s call regularly cuts through the musical texture.

- X. Volière

Virtuosic passages against a quiet background depict a bird in flight: the rapid runs, arpeggios, and trills mimic the bird’s facility in the air.

- XI. Pianistes

Saint-Saens presents a satirical view of pianists in this movement, who appear to be gracelessly executing tedious exercises reminiscent of Hanon or Czerny. This characterisation of pianists as caged animals in a practice room ordains their inclusion in the Carnival of the Animals.

- XII. Fossiles

In addition to heavily using material from his own symphonic poem Danse Macabre written more than a decade earlier, Saint-Saens also quotes melodies from popular folk songs, and an aria from Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. Leonard Bernstein speculated that the musical joke is that the pieces quoted were the musical fossils of Saint-Saens’ time.

- XIII. Le cygne

Perhaps the most popular movement of the suite and the only movement that was published in the composer’s lifetime, the swan features a slow, graceful melody which mirrors the peaceful movement of the swan through water.

- XIV. Final

The short introduction to the final movement begins with the same material heard at the very beginning of the piece. The bulk of the movement features a brisk, jubilant melody with a bouncy accompaniment, similar to music that might be heard at a carnival. Music from several of the preceding movements returns, including the swift animals, the hens and roosters, and the kangaroos, however it is the donkey appears to get the last laugh before the final chords: perhaps alluding to the composer’s anticipation that the work would be ripped apart by critics should it be published!